You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Official Car Thread

- Thread starter JackBootedThug

- Start date

Monkey Man

Super Moderator

Wow.

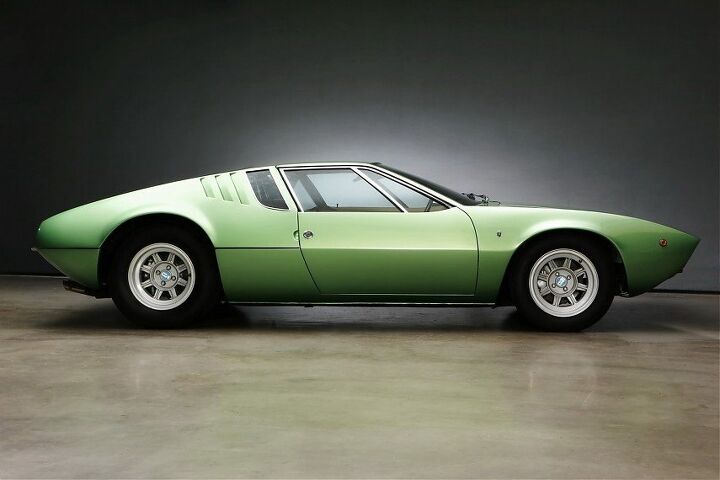

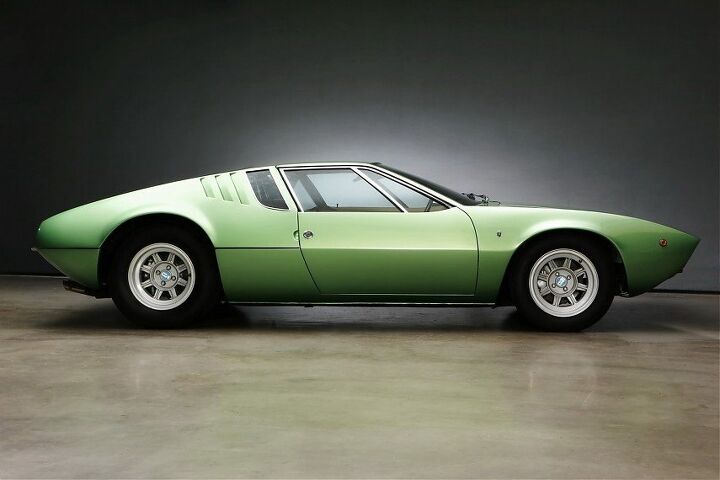

The Mangusta was successor to De Tomaso’s very limited production introductory model, the Vallelunga. Produced from 1964 to 1968, just 53 examples exited the factory in Turin Italy. Part of the reason so few cars were produced was that De Tomaso didn’t want to make his own cars. After the Vallelunga was designed by Fissore, De Tomaso planned to sell it on to a third party for production. However, nobody took the bait, so he farmed out production to Ghia instead. And a new car brand was formed.

@Monkey Man

The Bolwell Nagari is one of the most successful Australian cars that you’ve never heard of. Even most Australians haven’t heard of it. It was the eighth car produced by Bolwell and their first production car. All previous Bolwells had been kit cars. 100 coupes and 18 convertibles were built between 1970 and 74. This makes it the most popular and well known Bolwell, and makes Bolwell the second most successful Australian sports car manufacturer after racing car specialists Elfin.

Graeme and Campbell Bolwell started their company in a workshop in Melbourne in 1963. Before going to business, they built four prototype specials. Their first commercially available sports car was MkIV, named by Campbell because he believed no one would buy a guinea pig model. This was followed by the larger MkV. People had been fitting readily available six cylinder Holden Grey motors to the compact MkIV. The MkV was purpose-built to accommodate Grey motor sold alongside the MkIV until 1965, when the MkIV was retired. The MkV was replaced by the MkII in 1967. Officially the Mk VII only available as a kit car, but a handful were assembled by Bolwell. The Holden six powered Mark VII sold over 100 examples, perhaps as many as 400. Being a kit car from the 1960s, it’s difficult to determine an exact production number. It’s believed that there may be several kits in existence that were never assembled.

The Bolwell MkVII

The MkVI SR6 was a one off mid engined racing car built in 1968. That’s right, the MkVI came after the MkVII. The SR6 first raced in 1969 with a Repco-Holden V8 and modified Volkswagen transaxle,before receiving a 202ci Holden Red six cylinder and Hewland transaxle.

Following the launch of the Mk VII kit car, Graeme Bolwell went to the UK to work for Lotus. During his time there, Lotus made the transition from kit cars to turn key production cars. Graeme decided he wanted the same for his own company. Additionally Campbell Bolwell was concerned about badly built kit cars tarnishing the family name. Upon his return, Graeme applied what he had learned to the Mk 8 Nagari. The Nagari featured a backbone chassis and fibreglass body. The Nagari was often mistaken for a variant of the Lotus Elan, but while the two cars share a design philosophy with the same basic construction, they don’t actually share any components.The Bolwell chassis is entirely bespoke. The Lotus backbone chassis was designed to accommodate an inline four, whereas for the Nagari, Bolwell wanted a V8. To make room for a V8 engine the Bolwell backbone chassis differed significantly, with a Y shaped front section.

In their previous models, Bolwell had used Holden six cylinder engines. Their original intention with the Nagari was to continue that relationship and use Holden’s new 5.0L V8, but Holden refused. They started sourcing engines and drivetrain from Ford, who were happy to sell them some of their imported V8 engines. The Nagari ended up initially being offered with a 302 Windsor from the Falcon GS, or the 351 from the GT. When Ford switched from the Windsor to the Cleveland in 1971, Bolwell followed, modifying the headers and chassis to accommodate the larger engine. With the Cleveland installed, those distictive side vents, previously used for cabin cooling, were needed to cool the engine. The four speed toploader manual gearbox and 9 inch rear diff were also taken from the Falcon. Whichever engine you had in your Nagari, straight line performance was astonishing. With the Cleveland engine it was capable of exceeding 240km/h. Imagine if they’d had access to the GTHO version. Not all Nagaris had Ford V8s, some had Holden sixes and one had a 1.5 litre four cylinder from the Ford Cortina.

A Cleveland Nagari can be identified by its bonnet bulge

The Ford V8 was mounted as far back as possible

Much like its contemporaries, the AC Cobra and TVR Griffith, the Nagari’s handling was rather lairy. There was a fair amount of flex in the body. The relatively soft suspension, necessitated by Australia’s rough roads, didn’t help.

As a racing car the Nagari worked rather well. Despite their rarity, the Nagari was a popular choice of production sports car, with several of them competing in the Australian Sports Car Championship in the early 70s. The Nagari never won the ASCC, as the rules allowed for purpose-built Group A racing cars (essentially a low-budget Australian Can Am). It’s best result came in 1973. John Latham drove a Nagari to seventh place in the championship, making it the highest placed production car.

The Nagari’s undoing was it’s price. When it lauched, it cost $2,795 as a kit car, or $5,490 as a turn key model. In 1970, a Holden Kingswood cost $2,593. Even if you wanted to go racing, there were cheaper options. The Holden Monaro GTS 350 and Ford Falcon GTHO Phase II were cheaper propositions at $4,181 and $4,830 respectively. A Datsun 240Z was $4,567. Inflation was rapidly rising and by 1974, the price had risen to $9,990 for the coupe and $10,200 for the convertible. That was nearly Jaguar E Type money ($11,552). Few people in Australia were willing to pay that much for a fibreglass sports car with few creature comforts, but Bolwell couldn’t make them for less. New design rules meant that Bolwell couldn’t afford to keep going. In 1973, a left hand drive prototype was built, and there was excitement about plans to begin exports to California, but that never eventuated.

Following the Nagari, Bolwell returned to kit cars with the Ikara, a mid engined car using Volkswagen Golf mechanicals. The Ikara was the last Bolwell sports car. Bolwell elected instead to focus on the more lucrative composite materials business. Australian low volume sports car manufacturers had it harder than their British counterparts. 1970s Australian roads were rough, the population was small and race tracks were sparse.

The MkIX Ikara was the successor to the Nagari

The Toyota powered Nagari Mk 10

Today, Bolwell Nagaris have a cult following, but remain relatively affordable for their rarity. At the time of writing (2017) there is a 1971 302 convertible for sale for $89,500.

To see a Nagari in the fibreglass today, you’ll have to go to a major classic car show. The odds of seeing one on the road or at a smaller show are extremely small. Remember there were little more than half as many Nagaris as there were Falcon GTHO Phase 3s. The Nagari is an often forgotten and unrecognised car that holds a special place in Australia’s motoring history as one of our only production two seater sports cars.

A Nagari convertible at the Shifting Gear exhibition in 2015

Bolwell Nagari: Australia's Greatest Sports Car

The Bolwell Nagari is one of the most successful Australian cars that you’ve never heard of. Even most Australians haven’t heard of it. It was the eighth car produced by Bolwell and their first production car. All previous Bolwells had been kit cars. 100 coupes and 18 convertibles were built between 1970 and 74. This makes it the most popular and well known Bolwell, and makes Bolwell the second most successful Australian sports car manufacturer after racing car specialists Elfin.

Graeme and Campbell Bolwell started their company in a workshop in Melbourne in 1963. Before going to business, they built four prototype specials. Their first commercially available sports car was MkIV, named by Campbell because he believed no one would buy a guinea pig model. This was followed by the larger MkV. People had been fitting readily available six cylinder Holden Grey motors to the compact MkIV. The MkV was purpose-built to accommodate Grey motor sold alongside the MkIV until 1965, when the MkIV was retired. The MkV was replaced by the MkII in 1967. Officially the Mk VII only available as a kit car, but a handful were assembled by Bolwell. The Holden six powered Mark VII sold over 100 examples, perhaps as many as 400. Being a kit car from the 1960s, it’s difficult to determine an exact production number. It’s believed that there may be several kits in existence that were never assembled.

The Bolwell MkVII

The MkVI SR6 was a one off mid engined racing car built in 1968. That’s right, the MkVI came after the MkVII. The SR6 first raced in 1969 with a Repco-Holden V8 and modified Volkswagen transaxle,before receiving a 202ci Holden Red six cylinder and Hewland transaxle.

Following the launch of the Mk VII kit car, Graeme Bolwell went to the UK to work for Lotus. During his time there, Lotus made the transition from kit cars to turn key production cars. Graeme decided he wanted the same for his own company. Additionally Campbell Bolwell was concerned about badly built kit cars tarnishing the family name. Upon his return, Graeme applied what he had learned to the Mk 8 Nagari. The Nagari featured a backbone chassis and fibreglass body. The Nagari was often mistaken for a variant of the Lotus Elan, but while the two cars share a design philosophy with the same basic construction, they don’t actually share any components.The Bolwell chassis is entirely bespoke. The Lotus backbone chassis was designed to accommodate an inline four, whereas for the Nagari, Bolwell wanted a V8. To make room for a V8 engine the Bolwell backbone chassis differed significantly, with a Y shaped front section.

In their previous models, Bolwell had used Holden six cylinder engines. Their original intention with the Nagari was to continue that relationship and use Holden’s new 5.0L V8, but Holden refused. They started sourcing engines and drivetrain from Ford, who were happy to sell them some of their imported V8 engines. The Nagari ended up initially being offered with a 302 Windsor from the Falcon GS, or the 351 from the GT. When Ford switched from the Windsor to the Cleveland in 1971, Bolwell followed, modifying the headers and chassis to accommodate the larger engine. With the Cleveland installed, those distictive side vents, previously used for cabin cooling, were needed to cool the engine. The four speed toploader manual gearbox and 9 inch rear diff were also taken from the Falcon. Whichever engine you had in your Nagari, straight line performance was astonishing. With the Cleveland engine it was capable of exceeding 240km/h. Imagine if they’d had access to the GTHO version. Not all Nagaris had Ford V8s, some had Holden sixes and one had a 1.5 litre four cylinder from the Ford Cortina.

A Cleveland Nagari can be identified by its bonnet bulge

The Ford V8 was mounted as far back as possible

Much like its contemporaries, the AC Cobra and TVR Griffith, the Nagari’s handling was rather lairy. There was a fair amount of flex in the body. The relatively soft suspension, necessitated by Australia’s rough roads, didn’t help.

As a racing car the Nagari worked rather well. Despite their rarity, the Nagari was a popular choice of production sports car, with several of them competing in the Australian Sports Car Championship in the early 70s. The Nagari never won the ASCC, as the rules allowed for purpose-built Group A racing cars (essentially a low-budget Australian Can Am). It’s best result came in 1973. John Latham drove a Nagari to seventh place in the championship, making it the highest placed production car.

The Nagari’s undoing was it’s price. When it lauched, it cost $2,795 as a kit car, or $5,490 as a turn key model. In 1970, a Holden Kingswood cost $2,593. Even if you wanted to go racing, there were cheaper options. The Holden Monaro GTS 350 and Ford Falcon GTHO Phase II were cheaper propositions at $4,181 and $4,830 respectively. A Datsun 240Z was $4,567. Inflation was rapidly rising and by 1974, the price had risen to $9,990 for the coupe and $10,200 for the convertible. That was nearly Jaguar E Type money ($11,552). Few people in Australia were willing to pay that much for a fibreglass sports car with few creature comforts, but Bolwell couldn’t make them for less. New design rules meant that Bolwell couldn’t afford to keep going. In 1973, a left hand drive prototype was built, and there was excitement about plans to begin exports to California, but that never eventuated.

Following the Nagari, Bolwell returned to kit cars with the Ikara, a mid engined car using Volkswagen Golf mechanicals. The Ikara was the last Bolwell sports car. Bolwell elected instead to focus on the more lucrative composite materials business. Australian low volume sports car manufacturers had it harder than their British counterparts. 1970s Australian roads were rough, the population was small and race tracks were sparse.

The MkIX Ikara was the successor to the Nagari

The Toyota powered Nagari Mk 10

Today, Bolwell Nagaris have a cult following, but remain relatively affordable for their rarity. At the time of writing (2017) there is a 1971 302 convertible for sale for $89,500.

To see a Nagari in the fibreglass today, you’ll have to go to a major classic car show. The odds of seeing one on the road or at a smaller show are extremely small. Remember there were little more than half as many Nagaris as there were Falcon GTHO Phase 3s. The Nagari is an often forgotten and unrecognised car that holds a special place in Australia’s motoring history as one of our only production two seater sports cars.

A Nagari convertible at the Shifting Gear exhibition in 2015

Monkey Man

Super Moderator

Thanks for sharing bro'.

Last edited:

Monkey Man

Super Moderator

I know from experience in Gran Turismo over the years that the Tuscans aren't great at goin' 'round corners, but by crikey, can they rip down the straights.